Texts, Reflections, Poems, and Remarks

/https://dev6.siu.edu//search-results.php

Last Updated: Oct 18, 2023, 03:23 PM

Texts, Reflections, Poems, and Remarks on Conversation and Conversation 2

The following texts, reflections, poems, and remarks are responses to Conversation 2.0.

Texts, Reflections, Poems, and Remarks

University Museum Curator of Exhibitions' Statement

Much like the original Conversation exhibition (2002), Conversation 2.0 (2020) revisits the varied and dynamic works of Edna J. Patterson-Petty juxtaposed with traditional works of art from the Reginald Petty African Art Collection, thus, underpinning a powerful conversation between the Artist’s and the traditional works.

Walking through the exhibition, you are able to see two types of work on display, traditional African art and modern works of art. These objects are displayed in a way meant to establish a distinct line between traditional art styles and Edna’s works. This Conversation between the works establishes more than just Edna’s inspiration; it shows a deep connectedness with her history and a fundamental understanding of traditional art forms.

Through Edna’s works you are able to see clear references to traditional African art and crafts. This goes well beyond the simple repetition of traditional iconography or color schemes. The Artist is able to translate traditional aesthetics into powerful works of art. Combining modern imagery and traditional design aesthetics allows Edna to transcend any one medium, generating compelling works across multiple styles.

WM Weston Stoerger

Curator of Exhibitions

The University Museum

Southern Illinois University Carbondale

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

A Section of Conversation 2 in Atrium Gallery, University Museum, SIUC

Conversation 2.0: An Exhibition of Multi-connections

Conversation 2.0 is an exhibition of multi-connections: husband and wife, artist and collector, Africa and America, and past and present. The spiritual kinship of Reginald’s African artifacts (West and East Africa) and Edna’s Afrocentric creative mix-media works are powerful objects of African functionalism. There is a powerful link of information between African artifacts and African-American fine art. Artist and Scholar Dr. Samella Lewis stated: ‘Art is not a luxury as many people think – it is a necessity. It documents history – it helps educate people and stores knowledge for generations to come’ (Robinson, 2019).

The compositional layout of the exhibition gives logical thought of call and response throughout the gallery. As I moved through the exhibit, I was being intellectually and spiritually pull by the aesthetic conversation of traditional and contemporary African art forms I’ve experienced several times over the years at the Petty’s’ home. In this exhibit, one of my best experiences was witnessing the thematic conversation between Reginald’s wooden 20th century African antelope mask titled, “Bambana” and Edna’s contemporary mix-media sculpture of the male Ci Wara titled, “Bambana (Antelope Headdress). One of Reginald’s Ci Wara headdresses became damaged and Edna re-contextualized it as a sculpture form. When I asked about the creative process of giving new life to this damage Bambana art, Enda stated:

“Whenever possible, I enjoy recycling. The sculpture was broken andpieces were missing so I wanted to salvage it and give it a new life. I molded the broken sections with polystyrene foam. The fabric I used to cover the sculpture was hand-dyed. I think of the color blue as a source of healing. The broken bottle was tumbled to alleviated the sharpness, and it was glued in place around the sculpture to emulate a barrier of protection.”

Reginald and Edna had allowed us an opportunity to learn about the Bambana people and their elevated commitment to the life of farming. “The Bambana, who lives in the southern part of present-day Mali, have long considered farming to be among the most noble of all professions. Although many Bambana have adopted Islam over the course of the last century, theatrical Ci Wara dances continue in many Bambana villages, celebrating their agrarian lifestyle” (Clarke, 2006).

When thinking of these artifacts in this setting, the University Museum gallery, I see them as frozen moments that created distance between the artifact and their original purpose. Nowadays, it is common knowledge that these African artifacts were created for specific functions. They are objects of ideas, concepts, traditions, and beliefs coming from various African cultures; therefore, they are symbols of great educational importance within the African societies.

In the context of this exhibit, Edna’s Bambana Antelope Headdress operating in a different culture (American) and not functioning in its original purpose as an object of physical movement-- ceremonial dance, but is functioning as an object of intellectual movement (new life). This comes across in reminding us of the traditional ceremonial dance and its cultural importance, because:

“… the Bambana [‘s dances], that of the Tyi [Ci] Wara was never static, but rather one which evolved in form over the years under the influence of various individuals. It is impossible now, of course, to document what the characteristics of this dance were at various points in time in the past.” (Imperato, 2006)

When thinking of an important event such as the Bambana dance I am reminded of Ghanaian philosopher Willie E. Abraham statement on significant events:

“ALL EVENTS OF LARGE significance take place within the setting of some culture, and indeed derive their significance from the culture in which they find themselves. It could therefore happen, and dose indeed happen, that the same event, occurring as it were between the frontier of two different cultures, should be invested with differing significance . . .” (Abraham, 1969).

I believe Conversation 2.0 has allowed me to experience the investment by our ancestors, artists, collectors, and institutions in this continuous dialogue of African and American culture. The exploration of Reginald and Edna as Keepers of the African culture is quintessential of the African Diaspora. Conversation 2.0 provides a platform to challenge the cultural deprivation and dilemma faced by African descents in America. Thanks is due to Reginald and Edna Petty for the valuable work they have done for understanding of our past and for the betterment of our present and future.

Najjar Abdul-Musawwir, M.F.A.

Professor

School of Art and Design

SIUC

(Photo: Rusty Bailey)

Edna Patterson-Petty, Recontextualized Chiwara Headdress.

(Detail)

Reflections on the Art Collection of Reginald Petty and Edna J. Patterson-Petty

Ezekiel saw a “wheel on the earth beside the living creatures, one for each of the four of them. As for the appearance of the wheels and their construction: their appearance was like the gleaming of beryl; and the four had the same form, their construction being something like a wheel within a wheel. When they moved, they moved in any of the four directions without veering as they moved. Their rims were tall and awesome, for the rims of all four were full of eyes all around. When the living creatures moved, the wheels moved beside them; and when the living creatures rose from the earth, the wheels rose. Wherever the spirit would go, they went, and the wheels rose along with them; for the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels. “

[Ezekiel, 1: 15-20]

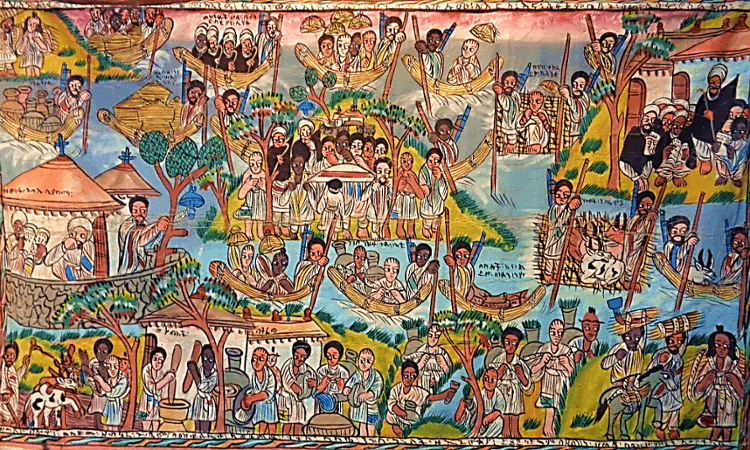

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Ethiopian Religious Painting

C20th. Paint on canvas.

52 x 24 inches .

Reginald Petty African Art Collection.

I.

Not only were the walls filled with creatures who stared back as we stared at them, not only was the space filled with chairs and pots and wrappings that pulsed with traces of the life in the hands that carved, molded, wove them; not only was the air filtered and fogged with color and light and scent

there were voices old and sonorous and querulous and approving.

Terra cotta and enameled lips. Wooden mouths honed and polished with knives, stones and cloth. Feathered filigrees of paint whispering sly jokes and incantations. Voices. Voices. Beginning at the beginning. Outlasting, out-laughing, out-admonishing and cajoling us to see the need and the beauty that coaxes need into attention.

II.

East St. Louis began talking to Ghana, to Zimbabwe, to Zambia, to the Yoruba, the Fon, the Hausa, long before the first stool was bestowed, the first trade-weight was pocketed; long before the first long-limbed spirit-filled wood dancer stood in the window looking across time.

Miss Helen said:

look as far as your eye and soul can see. Recognize yourself in the faces of strangers who have long passed into the valley of the dry bones and in the eyes of children who won’t be born until you are way past grown.

She said:

converse with the world. Know things and be known by your patience, generosity and feeling for family. Wherever you walk, bring back the stories of those you meet. And tell them where you came from, who knows you, and who your people are. This way and that: they all said: what we have taught you, remember. Connect and trace and figure.

She (and they) said:

teach. Always teach. And learn something, too. Put flesh into your dreams. Walk the earth.

III.

And then come home.

Home.

The afterthought of those (ever and always) who pushed/push on to some other destination and leave the dirty work of building, slaughtering, packing and moving necessities out of sight

until ready to be consumed.

Fling sin across the river (they said).

Keep the dirt and the disease out of our homes (they say).

Put it in one convenient place (they never say) where we can reach it when our bellies rumble and crave some sweetness that can be tasted only after hours

-of denying lying crying and signifying-

put the gin and the cards, the horses, the easy houses and the soft dreamy playthings where we can always ignore them.

But close (they say, with urgency and hypocrisy), always close where we can control them.

And what would home be

without the songs

the singers

the conjurers who could with their breath take

the torture out of pain and hungry beds

and smooth crumpled souls with sounds

making visions appear

everywhere

like wheels? within wheels?

Miles Davis. Grant Green. Clark Terry.

Left home and met

other sound-shapers who knew how to hammer

a note into the thickest heart and head

where even the strongest rye whiskey could not completely

narcotize the pain

Edna Patterson-Petty, 42 Days Till You (Miles).

1996. Quilted Fabric and beads.

22 x 20 inches.

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

[wheels of music leap across the space of the walls

one quilt enjoining night life quilts to shimmy crackle and shake]

Dunham daylight-danced through

sprinkling ancestor goofwa dust in the eyes and ears

of children

stretching their bodies to “fly without ever leaving the ground

Dumas slid up river from Sweet Home, Alabama, heard

something soft and sensual in the sounds of rain

steaming up from the streets in the July sun

and added his words to the gumbo pot

[behind all of this moving up and down the road

is the home grown beret-capped

Papa Legba who smirks at the bus station

train station way-station

river dock

reading-man Redmond:

nobody knows the trouble they see

until the poetry man can smack eyeballs into word clouds

rising up like wheels? yeah, like wheels

ropes and ladders]

visions and voices

and songs and dances

home-grown

home

the world met at the riverside

and Reginald Petty

took the first chariot

to the homeland

that had room for him

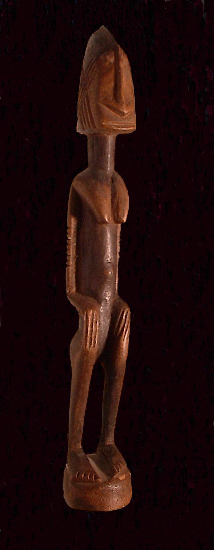

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

C20th. Wood.

2 x 2 x 8 inches.

Reginald Petty Colletcion.

IV.

“Legba must always be given recognition, whether in Africa or the New World, though Legba is not recognized as a loa in the strict sense of the word. In Ibadan, Nigeria, in Cuba, in Brazil, and in Haiti I have called upon Legba to open gates for me, to open the barrier between my petitions and the supreme:

“Papa Legba, ouvrié barrié pou moi, la vie nou mandé, nou mandé bien!”

“Papa Legba, open the barrier for me, life sends good things for me.” Or it could be that life demands good things, depending on how the creole is translated.

I like the first translation. Legba is polynational, serving, among others, Yorubas, Arada-Dahomeans, Ibos, Nagos, Congos, as gatekeeper or spirit intermediary between humans and true gods. He seems to be as strict as Saint Peter in judging entry into the promised land, but, by reputation, he is easily bribed or cajoled.” (Katherine Dunham, Island Possessed, page 119)

Yoruba Terracotta Head

C20th. Terracotta.

4.5 x 6 x 10 inches.

Reginald Petty Collection.

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

If you wish, Legba can be considered a “crossroad” deity [loa], but for the purpose of this exhibition, Papa Legba can be understood as a “threshold” god. Walk into the space and you enter a world within a world. We could not leave the larger world, disconnect ourselves from whatever reality through which we waded into the gallery. Walls of windows, open doorways, precluded such hermetic retreat. The walls created their own special effects: Clean, elegant, simple masks were hung next to animal masks positioned to crawl up or down the walls. Across from these wooden stabiles, there were quilts and fabric constructions which were three-dimensional in the cross harmonies of colors, mixed cloths and accessories. Glass, wood, paint, metal, clay (rough and ceramic), caused the eyes to spin, the mind to whirl, the breath to quicken and stop.

Choose?

Legba opens the barriers. Choose.

You cannot choose.

You can only accept all of it, simultaneously.

Like any good drum dancer would know.

[Sometimes the game is seek-and-hide:

Look at the drum. Is there a spirit?

Where else would Legba lurk?

V.

the wheels rose along with them; for the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Baga Poro Bird Mask.

C20th. Wood and Paint.

14 x 16 x 25 inches.

Reginald Petty Collection

VI.

“Accordingly, in many arts of Africa there is meaningful concentration on moral representation. However, there is more to the “person” than facial calm; not only must he or she be physically strong, and dance and dress with energetic flair, but the person must also show, ideally, metaphysical powers of insight or revelation, a sense of humility and concern before unseen sources of vitality.... Being a person is also being mystical, being endowed with a rightful thirst for transcendence of human limitations. The point is liberation. Self-realization in a transcendent mode immediately identifies the proper elder or the proper chief.”

(Robert Farris Thompson, African Art in Motion, pages 120, 125)

A thirst for transcendence is what pulls us to the walls, to the figures of mothers nurturing with their breasts, to the challenge of men displaying every ounce and inch of their power and life force. The antelope, the alligator, the hyena, suspended in the air, teach us to be ready and open.

And they teach us to look within, introducing ourselves, muntu to muntu, to power

“The extraordinary person in West Africa is sometimes spectacularly associated with horns. The power of nature is honored in great horns, upraised.”

(Thompson, Motion, page 133 ff)

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Bobo Mask.

C20th. Wood and Patina.

14 x 12 x 34 inches.

Reginald Petty Collection.

Suspend. Transcend. Thirst. Elegance. Humility.

More to coolness than calm.

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Ashanti (Akan) Terracotta Head

C20th. Terracotta.

5 x 7 x 11 inches.

The Reginald Petty Collection.

How, do you suppose, could one survive dances at the Vets Club in East St. Louis and

the dance halls of Ouagadougou without

the ability to fake the cool

until one learned it?

What is in the masks? Living spirits. Whose?

Yours.

If you pay attention to the voices.

“Thus the closing of the eyes and the freezing of the face in one form of Akan possession in Ghana can be compared to the closed eyes and cold features of a Baoule mask. Even more to the point, the backward tilt of the head in Akan possession and statuary is sometimes compared to the proverb, ‘face looking down shows sorrow, face looking up shows ecstasy and trust in God.’ It is important to add that some Akan terra cotta heads represent priests or priestesses, specialists in possession, and many of these show the ecstatic angle of the head.”

(Thompson, Motion, page 126)

Face looking up sees

joy sees

truth

sees hope

balance

in the face

of broken dreams

sees death and will never forget

such power to live

Rising up, we see the faces of heroes, those we know, Mandela, Jackson, Malcolm, Martin. There is nothing cool about the fractured faces, the disconnected lives, the exploding tattered dreams. There is everything there: we must find the balance. We must reconstruct our own, supply our own, become our own....

There is nothing for it but to dance.

She is being transformed by the spirits he brought into the house. They watch her, call her daughter, mother. She cares for the children. She has always heard the voices. Sitting around the quilting table, she absorbed the murmuring stories. The wind of women’s voices. She plays them like drums. Each beat a color, a shape, a shard. Each dance within the fabric breaking the stitch, shattering the frame.

That is the secret.

Confront the dance.

Become the butterfly-angel-spirit-guide. Awesome and terrible.

No resurrection takes place without stones being blasted into dust.

Rock-a my soul in the bosom of Edna

Let her fingers re-design cosmic jokes

that have more respect than a forest of children

bowing down before the elder ghosts

Even the chairs conversate

big old girl with too much everything

splay foot and gap-legged looking loud and common

Looking for all the world like she belongs, towering over the stools of the ancestors

the stools (who are ancestors) protect the young girl who speaks so softly and plays her woman game in the middle of the room

Around the tree-of life, holding the water for the evening meal, we carry you in our embrace.

We dance.

We carry you in our head. We carry you. In our head.

We demand.

You dance.

Are you drunk enough to let go?

Are you dizzy with colors?

Have we told you enough about yourself that you have seen how to spin like sand in the roadway during the storm? Have you tasted the color red on your tongue, felt the color blue on your brow? Have you felt crowded in the boat with all the strangers who can fit?

Do you wish to blanket yourself with your past

And rest

VII.

“Learn the positive events of one’s racial family, and family history

Learn to plan for the future. It is important to have knowledge of the past upon which to build.

Open all of your senses to the arts

As early as possible develop a God sense; details can come later

There are many gates to Heaven

What you will learn in life relative to the whole is minuscule

Accept it

God will find you at the strangest times, places

Just be open

Genuine love will cross racial, cultural, or ethnic lines if you are open to it

be open”

(Reginald Petty, Memories of Days Gone By)

VII. [Again. You can never have too many 7s.]

Oh. And one thing more:

Never turn your back on art

(Legba can sneak into your pocket)

Mind my sister, brother, how you walk on the cross.

It could turn into a wheel

And then where would you be

Way up in the middle of -

Exactly

- Luke

Joseph A. Brown, SJ, Ph.D.

Professor

Department of Africana Studies

SIUC

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Ruminations on the Arts of Africa

In what, for me, has become a classical example of robust exegesis on the state of African art in the 1970s, Africanist scholars engaged themselves in the spring of 1976 attempting to define African art [1]. Among the academic titans who devoted considerable thought to this fugitive idea, and whose insights remain as luminous today as they were then, are Roy Sieber, Frank Willett, Herbert M. Cole, Susan Vogel, Simon Ottenberg, and Mailyn H. Houlberg. Central to the discourse were the constituents of fakes, forgeries, and authenticity.

Cole posits that the value ascribed to African art by the Euro-American art market stems more from what he calls “apparent age,” which is the patina acquired by any particular piece as a result of use, than from any authentic collection date (Cole 1976:22). In his own contribution in the same issue of African Arts, Robert Plant Armstrong was unambiguously declarative: “Fakes do not exist except under the circumstance that there are collectors.” Roy Sieber, whose reputation for spotting “authentic” art was widely acknowledged by peers and collectors, acknowledges that we tread on slippery grounds when it comes to determining with any degree of exactitude what is fake in African art. He cautions that “... it should be remembered that one cannot prove a piece is real; at times-but only at times-but only at times-one can prove a piece is wrong.” (Cole 1976:24)

When I arrived at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, to share some insights with an audience on African art-a topic so broad as to allow for innumerable permutations in the affective and the cognitive domains of the arts-I spent some time viewing the exhibit that provided the rationale for my invitation. Although I had been informed that the exhibit was from the collection of Reginald Petty and Edna Patterson-Petty, the one a devoted collector and student of African culture, the other a qualified artist and art therapist, I went to the gallery expecting to see the familiar. I had visualized an exhibit of modest status, much of it of recent pedigree. I had expected to see items that constitute the usual staple of university museums whose primary interest is not African or, to use a phrase that I detest, “non-Western” art: cones and gourds, caryatids, trays and other appurtenances of divination, votive figures and beaded things, arranged according to the whims and dictates of Leonard Gadzekpo, the curator.

Some of the items on my imaginary list were there. But so were other works that can be classified as African art only by spiritual association. They were the handiwork of Edna Patterson-Petty. The exhibit in this regard was positively nonconformist. What Paterson-Petty has done was to appropriate conceptual and stylistic elements and invest them with her own aura. In her creative response to the commanding presence of the works collected in Africa by the husband, Reginald Petty, Patterson-Petty found ways to temper the aggressive poise of African objects, to calm their accent and appease their spiritual energy. In the process, she produced works that represent kindred essences.

My mind went to Frank Willett, whose brilliant conjecture in the 1976 edition of African Art that I referred to earlier continued to haunt me. In his analysis, Willett drew up numerous sub-categories to the “false dichotomy”- thesis, all of which challenge us to recognize that we are perhaps prisoners of our own aesthetics. In Africa, the beauty of artworks is measured not necessarily by whether it is “authentic” or “fake,” “old” or “new,” but by standards that Western aesthetic paradigms are yet to fully account for. In a way, this has a faint echo of the situation that the world found itself in one century ago, before Pablo Picasso's tribe succeeded in changing entrenched prejudices about the status of African art. Is it possible that the Western world is years behind Africa in its aesthetic concept? What would Willett say upon seeing Edna Patterson-Petty’s work: is this “African,” “African American,” or “other?” (fig. 52) How do we rationalize the aesthetic thrust of her work? How do we classify, for that matter, the work of African American artists, including Aaron Douglas, Lois Mailou Jones, Faith Ringggold, Melvin Edwards, Rene Stout, Bettye Saar, and Jeff Donaldson, for whom Africa remains a bountiful spring of inspiration?

In spite of the remarkable insights offered on African aesthetics by, among others, Robert Farris Thompson, Roy Sieber, Henry Drewal, Philip Ravenhill, and Rowland Abiodun, a vast chasm exists in the scholarship of this subject and in the way that we tend to universalize art. Without deference to the total context within which African art is produced, our appreciation of the genre will most likely remain superficial. Without an understanding of the principles that warrant the creation and use of art in traditional Africa, we are ill-equipped to respect the creators of the pieces that we gawk at. Why do Africans venerate some art works, caress, honor, and even wear them while, in the West, most art works are set on a temple to be admired from a distance? What does it matter to the Dogon in Mali if there is a slight chip on the edge of one of the arms of a kanaga mask that is being danced? What does it matter that, among the Igbo in Nigeria, a bonfire is made of an ineffective ikenga piece? And in contemporary times, why would a Yoruba mother of twins who have since died, use imported plastic dolls in place of ibeji carvings? Since most art objects that are used in connection with religious and spiritual ceremonies are commissioned, fakery becomes a non-issue. And where, as has become fashionable in recent times, one is constrained to purchase any required item on the market, it is the essence of the piece, its signification rather than any concerns for authenticity that becomes the focal point. Within this context, the function of the piece takes precedence over other considerations such that even a “fake” piece of art, or a poor copy, can acquire legitimacy.

C20th. Wood, Beads, and Patina.

2 x 2 x 6 inches.

Reginald Petty African Art Collection.

In viewing the Carbondale exhibition, I came to the conclusion that our preoccupation in the field with fakes and forgeries, authenticity and hyperbole are, to lean on Robert Plant Armstrong, relevant mainly to collectors. Should university museums be dragged into this matter? Should colleges refuse donations of African art on the hunch that the objects have not been “used” in the parent culture? I believe that university museums have a responsibility to align their attitude with a progressive educational mission that values diversity, multiculturalism and plurality. To collectors should be conceded the right to hanker after the most exquisite objects. There should be little discussion about the fact that collectors earn the pleasure to enjoy their conquests and many are, indeed, benefactors of private and public institutions.

The discussions on fakes and forgeries should neither intimidate university museums nor stampede them into rejecting works that could be set aside for educational purposes. A good copy of Senufo sculpture, a faithful replica of a Chi Wara, a dignified re-creation of a gelede headpiece: any of these could be used as laboratory prototypes and with salutary results. A contemporary rendition of a Benin Oba's head or a terracotta look-alike ascribed to Ife could be productively utilized as educational tools in university museums. The essence of African art transcends the gorgeousness of the objects or their antiquity. Whether genuine or copy, African art, particularly in a university setting, has the uncontestable potential of engendering conversations. It has a transformative power to mold impressionable minds, sensitize them to their own unacknowledged prejudices and expose them to systems and world views that are manifestly different from theirs.

Yoruba Gelede Mask

C20th. Wood and Paint.

11 x 12 x 15 inches.

Yoruba Gelede Mask

C 20th. Wood and Paint.

15 x 15 x 19 inches.

(Photos: Leonard Gadzekpo)

The Reginald Petty Collection.

Some of the purposes of art are to entertain, enlighten, challenge, stimulate, and shock. In an educational setting, the display and study of African art is unquestionably one of the most effective, fun-filled ways of promoting understanding and fostering respect and appreciation for other cultures. African art provides an engaging platform through which students can obtain insights about the existence of other worlds. For students who have come to internalize the media hype, best exemplified in sports, to the effect that there is only one world, which is spelled U. S. A, the arts become an invaluable tool for introducing the existence of other worlds; they become passports that facilitate journeys into the astonishing recesses of the African continent. The beauty of African art lies in the fact that it provides us with windows through which we can glean a look at other existences. What is the connection between religion and art, for example? Indeed, should we not talk of a multitude of religious practices, rather than “religion?” How deeply embedded within the social fabric is art? What is the connection between ancestral veneration and annual festivals? What is the status of women and how does art mediate conjugal relationships? How is art an instrument in social organization, health care delivery, and the enforcement of law? The fact is that art is central to various situational mileposts: birth, initiation, education, marriage, social responsibilities, and final transformation.

Through the arts of Africa, we learn about the sum and substance of diversity. We learn about the criticalness of art to an understanding of traditional religious, social, educational, and political systems. We appreciate, above all, that much of the art is not decorative; that it is deeply entrenched in African systems of thought, and becomes intensely relevant in the socialization process; in the judicial systems and in health care management. From the cradle to the grave, African art is performance art. While it may be used to symbolize social class and authority, to confer aesthetic prestige on personages or institutions, it is also very much tied to instances that, in Western societies, have very little to do with art. Within this context, African art is art for life's sake. In terms of performance, the arts of Africa manifest extremely fluid boundaries and interrelationships. To perceive a mask, for example, is to enjoy the music, dance, poetry, and costumes that accompany its performance.

Although we refer to them as African art, if only because they originated in Africa, their purposes, uses and histories are as rich and varied as the styles in which they are made. When we visit museums to view African art, it must be borne in mind that what we often see is only a fraction of the total object. When we appreciate quilted textiles or appliqué works used by masquerades, it should be understood that these were items in what used to be a vibrant performance staged by human beings who, through appropriate agencies, have been transformed into mediums of communication with ancestors. Despite the strategies employed in major museums to present African art in its totality, the fact remains that African artworks in Euro-American museums are no more than decapitated spirits. Certainly, many who are privileged to view the arts in museums are touched by their visual presence, their aesthetic power and formal attributes. But these do not compare with seeing the works in actual context. Masks are more than simple carvings, and masquerades embody much more than colorful costumes. In real time, masqueraders command an impressive aura, particularly where music, dance, and poetry are invoked during performance.

As for the makers of these objects themselves-the artists and performers who give life to the works-they are men and women who have gender-specific roles: specialists who acquired their skills either within their lineage, or through the apprenticeship method. It is customary to find that the blacksmith who made the implement used by farmers on their farms was the same person who created the emblems used by various age groups or religious associations. This could also be the same person who carved the house-posts used to decorate the palace of the ruler, and carved the spectacular masks worn during the annual festivals. This blacksmith/carver could also be a herbalist with specialization in curing common ailments. His could also be an important voice in the way local politics is played. Because the distinctions that are made in the arts are fluid, crossovers are common. This attitude also extends to the way that categories are constructed within the arts. The distinctions that we make in Euro-American culture regarding high art and craft are hardly applicable in traditional Africa, since function and form are prized interchangeably.

In traditional African cultures, considerable emphasis is placed on fecundity. A marriage is not considered successful until the woman has had children. A man is considered unfulfilled who died without children. This fecundity is not limited to human reproduction. Since most societies are agrarian, agricultural fertility is also very essential. But what if a woman were to be barren and a village were to be ravaged by a drought? Enter the diviner. He would be consulted to divine the cause of this social malady. Invariably, the prescription involves the creation of a work of art, to be used as a votive. Concomitant with the issue of fertility and increase is the idea of respect, continuity and survival. The belief is strong in many African cultures that ancestors are the living dead who use their otherworldly powers to mediate between. the living and the dead. It is the need to pacify ancestors, to supplicate and memorialize them that is at the center of masquerades. Regarded as ancestors reincarnated, masquerades offer perhaps the best example of African art as performance art and total theater.

In a stealthy way, it would appear that in Euro-American societies, museum-goers have been primed to think that African masks are gorgeous and cute artworks. This is often a misleading notion, as masks derive their beauty from how effectively their characters are portrayed: how hideous or intimidating, how friendly or athletic, how spiritually powerful, they are. Some masks send chills down the spines of uninitiated onlookers. In many instances, women are forbidden from setting eyes on certain masquerades. Through masks, it is possible to appreciate the virtuosity of the carvers who sculpt some of the most intricate, often larger than life, pieces all from one piece of wood, without the aid of any sketches, nails, or glue.

Given the onslaught of modernity and the infusion of Western ideas, the production of some traditional sculptures has declined considerably. Western education has radically changed the apprenticeship system through which artists learn the trade, while the introduction of cash economy has altered the concept of patronage. In spite of these changes, masks as a genre remain popular. Their popularity is a testimony to the resilience of African art, and its ability to adapt and re-define itself.

The inroads that Islam and Christianity have made combined with Western education and the growth of technology compel modification of masking traditions on the African continent. Stripped of the original context that regulated the production of masks in Africa, what emerges is art that has become truly contemporary: enjoyed essentially for its aesthetic rather than religious or apotropaic significance. In a way, the exhibition, Conversation: African Art from Reginald Petty Collection and the Works of Edna J. Patterson-Petty did justice to the fundamental issues at stake. It facilitated a series of conversations, students, faculty, staff, and the lay public were afforded the opportunity to view African art, and to appreciate the creations by Edna Patterson-Petty. Education consists in gestures like this: bringing Africa to people in a way that stimulates visual perception at the same time that it allows them to question age-long assumptions about the people of the African continent.

Dele Jegede, Ph.D.

African Art/Art History Consultant

Professor Emeritus

Miami University, Oxford, Ohio.

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Masks

The Reginald Petty African Art Collection.

[1] See African Arts IX (3) April 1976 for a comprehensive dialogue on this topic.