Africana Textile Art Tradition

/https://dev6.siu.edu//search-results.php

Last Updated: Oct 18, 2023, 03:23 PM

In the highlands and plains of South Africa, the Ndebele, the Nguni, and the Zulu, just to name three ethnic groups, transform cloth, beads, leather and blankets into works of art, shawls of beauty, like murals on walls of beauty of their homes, textile art to cover their bodies. The Ashanti and Ewe weave exquisite Kente cloths worn at august ceremonies and Kente is the official traditional attire for most Ghanaians. Elegant and multi-colored Gelede and Epa masquerades swirl through streets in Yorubaland, and in Dahomey, where multicolored appliqués hang to announce status, coats of arms. In Elmina, under the shadow of a now-very-empty slave castle, the Asafo groups, companies of Fante warrior-dancers, who now only perform and enact war flag dances, attest to a textile art tradition that is an integral part of African life.

It was through horrendous voyages across the Atlantic Ocean in bowels of monstrous slave ships filled with stolen cargo of Africans that lasted over three centuries into the 19th century, starting out from dungeons of slave castles doting the coast of Africa, the oldest in Africa in Elmina, Ghana, that the African Diaspora was engendered and with Africa South of the Sahara emerged as Africana. From those dungeons, millions were brought in chains to the Americas to work on plantations and enslaved. The Middle Passage did not destroy vital cultural memory so that African textile art tradition made its way in the minds of stolen ancestors of Africana to the Americas. Many African Americans reclaim their African heritage and use Kente as one of the symbols of the reclamation. Carnivals in Brazil, the Caribbean, and in the United States, especially in New Orleans, epitomize not only Africana textile art in full display but also evidence re-interpretation of ancient African performance tradition in the Americas, the ancient and the modern forged in Africana performance.

Africana Textile Art Tradition

Quilt from South Africa

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Quilt from South Africa

C20th. Quilted Fabric.

114 x 144 inches.

Reginald Petty African Art Collection.

Africana

Africana

Africa carried us in her womb

for millennia at the dawn of humanity

before the stony pyramids rose,

human mitochondrial DNA the proof.

Standing in the Atlantic, in Bahia, Brazil,

calling the ancestors,

standing on the hills of Kingston, Jamaica,

dreadlocks stretch

across time and ocean

to Sheba, like the Nile,

to time before the contemptuous days

in the bowels of monstrous ships,

on watery graves of the Atlantic Ocean,

but even older, to the time

of bleached bones across the Sahara

and humanity disposed of from dhows

into watery graves of the Red Sea

and the Indian Ocean, of the Mediterranean,

before, and we saw the ways

of the crescent and the cross,

We have the Books and they the land,

after, men on horses and camels

rode across the desert into grasslands

with swords and spears in hand,

after, the Brandenburger and the Long Dane

served their time taking millions, cannons

and the Gatling, thousands upon thousands

of acres: the forty acres an empty promise.

We were on Amistad

and embraced Cinque.

We were Toussaint Louverture

and Harriet Tubman

leading like Moses.

We were Frederick Douglass

speaking the truth to power.

The Garveyite Black Star rose

when Nkrumah said:

The independence of Ghana

[Freedom] is meaning-

less, unless

it is linked

with the total liberation

of Africa,

Africana.

Du Bois evokes Pan-Africa

because Africana carries us.

Malcolm X is our manhood,

MLK our will and peace.

New Ancestors!

Our ears were cupped to listen

across time and ocean

to kith and kin

lynched.

George Floyd died breathless VIDEO:

under a knee on his neck,

like the knees of local, national,

and international systems

on the neck of Africana

for more than Five Hundred Years,

starting over a Thousand Years ago.

Darnella Frazier, as did many,

sisters, mothers, and communities

for centuries, saw it all, 8:48 minutes,

five feet away from horror and evil,

and recorded it for all to see,

saying of George Floyd’s murder:

“It’s so traumatizing.” We all are traumatized.

Emmett Till and Travyon Martin were killed

and trauma was inflicted on parents and Africana,

very fresh in memory as if just yesterday or today.

A sigh of relief, for at least, one survived

riding a bicycle to a basketball practice while black,

so too Lolade Siyonbola, napping on a campus

while black, but the trauma continues.

“Can we all get along?” asked/pleaded Rodney King.

We were in the Zanj Rebellion

and stood with Gaspar Nyanga,

Alonso de Illescas, Zumbi dos Palmares

and Dandara too, just as we did

with Nzigha Mbande and Yaa Asantewa.

Massavana led us all the way to Robben Island

like Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu.

We were in Stono and New York City,

and with Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey,

shoulder to shoulder,

and with Nat Turner, a week before

John Brown and his two sons,

Watson and Oliver, became our brothers,

Brown saying “mingle my blood further

with the blood of my children

and with the blood of millions.”

We sailed on Admiral Robert Smalls’ ship

and fought alongside General Harriet Tubman.

We took a train with Homer Plessy

while black

and saw Rosewood and Tulsa burn.

Montgomery, Birmingham, Watts, etc.

Jasper, Texas, Pain! Oh Pain!

Our ears were cupped to listen

across time and ocean

to kith and kin

shot,

Amadou Diallo, standing on his apartment

front stairs while black,

41 shots,

Walter Scott in the back, while black,

Philandro Castile, driving while black,

in presence of his partner and little daughter,

Tamir Rice, just a child playing while black,

and Breonna Taylor, sleeping while black.

A 911-call from someone

reported a suspicious person:

Who are the “someones”?

The “someone” is not criminalized,

but the suspicious person is killed

before proven guilty or innocent.

Within the law,

the season has been opened for centuries.

De jure, just play ball and play by the rules.

De facto, is it open season?

Self-righteously firing volleys

from word cannons,

some run wild and self-deputize,

armed as through all these centuries,

now with Colts and ArmaLite AR-15s,

but bloviate about democracy

and property rights.

False Property Rights for centuries enslaved,

undermined democracy, killed, divided,

and caused war, brother against brother:

“three-fifths of a person.” 3/5 is not 1.

Let there be equality, justice, and peace.

Africana stands on the rock of equality, justice,

non-violence, love, forgiveness, and peace.

In flight from American brothers

and other brothers around the world,

wading in the waters,

Jacob dreamed: Jacob’s Ladder.

This cannot be and it is not

Blake’s image of Dante’s Inferno.

Jacob Blake shot 7 times in the back,

leaning into a vehicle and looking into the faces

of his three young sons,

next generation of Africana men,

who saw all the horror:

“Papa, why did they shoot my daddy in the back?”

“Where’s daddy?” three generations in anguish,

like young Olaudah Equiano

saw his parents brutalized and

community traumatized and decimated.

Gabriel Crump spoke centuries-old

pain and suffering:

“They will be traumatized forever.”

Shackled? Handcuffed?

Permanently or temporarily paralyzed

or killed

for being black? How many centuries?

So like Eric Garner,

breathing while black,

Elijah McClain did not survive

a breathless chokehold

and an injection of ketamine,

breathless and sedated to death,

walking while black,

listening to music and dancing.

The Gilliam Family survived,

but were forced at gunpoint,

two eloquent and beautiful daughters

handcuffed, traumatized,

next generation of Africana womanhood,

to lie facedown

on hot parking lot asphalt

because a motorbike license plate

morphed magically

into that of a SUV in Aurora.

“I want my mother,”

like Wheatley’s

“sorrows labour in my parent’s breast.”

“Can’t I have my sister next to me?”

like centuries-old separation of siblings

in Africa and in the Americas or in Europe

or in Asia Minor.

Teenage girls’ voices expressed pain and anguish,

but were of fortitude and overflowing with love,

but the trauma persists.

Aurora, like other auroras of the world,

not awesome and beautiful spectacles,

was the result of a disturbance

in the magnetosphere of power and arrogance

caused by the wind of inhumanity and injustice

strong enough to discharge bullets and horrors.

For Africana, does death by “excited delirium”

happen only under a knee or through bullets

or under what Wheatley calls “tyrannic sway”?

USA: Ida B. Wells spoke unfazed and fought

against lynching and terrorism

against Children of Africana Womanhood.

“To those who oppose us, we say,

‘Strike the woman, and you strike the rock’.”

South Africa: Winnie Madikizela spoke.

USA: Shirley Chisholm spoke.

Jamaica: Portia Simpson-Miller spoke.

Brazil: Benedita da Silva spoke,

(statistically, 100% of blacks are not poor),

but like wealth and privilege:

“Power is never shared/ not given away/

power is taken/ it’s not easy/ I always say.”

Like Frederick Douglas said:

“Power concedes nothing without a demand.

It never did and it never will.”

“Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

Name call? Call the names.

What is evil? Why is evil possible?

Is evil an order issuing from a spiritual being or entities,

or an order from a leader, or a group or society?

Is it the system or systems?

But systems are human creations

and are not devoid of human foibles.

Who created the system or systems and what for?

Evil is human machinations or schemes

that involve knowingly doing horrendous harm,

but relentlessly, vengefully, and unforgivingly

target the victim or victims of inflicted suffering,

when they stand up against their oppressors

who then offer justifications, arguments, and excuses

for human suffering and continue perpetrating

and wallowing in those actions unabashedly and gleefully

for personal and/or group self-aggrandizement and benefit.

Blood, sweat, and tears were first distilled

into sugar, smoked like tobacco, burnt

like molasses and brown like cacao,

then bleached white like bones of millions,

but more like cotton,

then through the alchemy of greed

transmogrified into gold with a golden rule:

From he who has the gold makes the rules

To those who have the gold make the rules.

USA: # Tarana Burke speaks.

#Patrisse Cullors/Alicia Garza/Opal Tometi

speak, continuing centuries of struggle

in the present into the future.

Not a four-letter word,

2020, despite being annus horribilis,

is crystal-clear vision

and an undeniable clarion call.

With wounds, calluses, and scars of the centuries,

but, as said through the centuries,

“Feet, don’t let me down, more miles to go.”

This is not Onesimus’ 1721 in Boston,

neither Wheatley’s 1772, nor 1619, but 2020:

Africana, “forward ever, backward never.”

America, forward into a still brighter future

upholding three greatest words: “We the People.”

Barack Obama was president

while black and is our empathy,

compassion, and intellect.

John Lewis is our moral fortitude

and our commitment to freedom,

justice, equality, and love of humanity.

Tutu is our muntu,

ML King, our voice, peace, and love,

Mandela our mantra,

our will, our humanity.

Yes, Africana still carries us.

Struggle for freedom and time did not separate but brought Africans and those in the Diaspora closer together. It also means the identities of these peoples are hammered out of resistance to oppression and imprinted with resilience in face of almost half a millennium of negation of their humanity and peoplehood. Africana is made of many nationalities, of people who are steep in patriotic allegiance to their specific countries, while vested in true freedom and equality of all humanity and upholding that humanity and dignity for African descended people. An ivory carving given to Reginald Petty in Botswana signifies newer bonding taking place among Black people, Africana, on both sides of the Atlantic after centuries of forced separation. The figures’ elongated ears and carved clock mean “we are listening for your return” (Petty, 2001).

During the Organization of Africa Unity (OAU) conference in Addis Ababa in 1963, African Heads of State followed closely events in America, especially, the May 1963 Birmingham riots. In their final communiqué, they sent an open letter to President John F. Kennedy with a congratulatory message on America’s success in space and most pointedly stated that:

The Negroes, who, even while the conference was in session, have been subjected to the most inhuman treatment, who have been blasted with fire hoses cranked up to such pressure that the water would strip bark off the trees, at whom the police have deliberately set searching dogs, are our kith and kin … The only offense which these people have committed are that they are black and that they have demanded the right to be free to hold their heads up as equal citizens of the United States (Mugabane 1987, 201).

Martin Delany, one of the African Americans who John McCartney called Pan-Negro Nationalists, more than a century earlier wrote, “[E]very people should be the originators of their own schemes, and creators of the events that lead to their destiny" (McCartney 1992,16). Toussaint L’Ouverture, Cinque Sembe, Richard Allen, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman and Ida B. Wells said it with deeds. Kwame Nkrumah, Nnamdi Azikiwe, Rosa Parks, John Lewis, and Martin Luther King, Jr. also said it in deeds, to name a few. Langston Hughes’ words stream down ancient rivers of Africana consciousness in The Negro Mother and Freedom’s Plow (Hughes 1961, 288-289, 291-297).

In early September 2001, during the United Nations Conference on Racism in Durban, South Africa, Africans and a large majority of those of African descent in the Diaspora presented a common stance on issues of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, slavery, colonialism, and systemic racism. What aspects of their experiences informed a unified position beyond the obvious color of their skin that comes in all the shades, from very light to real dark? Are there cultural values that generate their understanding of freedom, community, and the essence of life? If African art offers insight into the ethos of Black people, Pieces of a Dream and other art pieces created by Edna Patterson-Petty give us clues to a deeper understanding of contemporary Africana

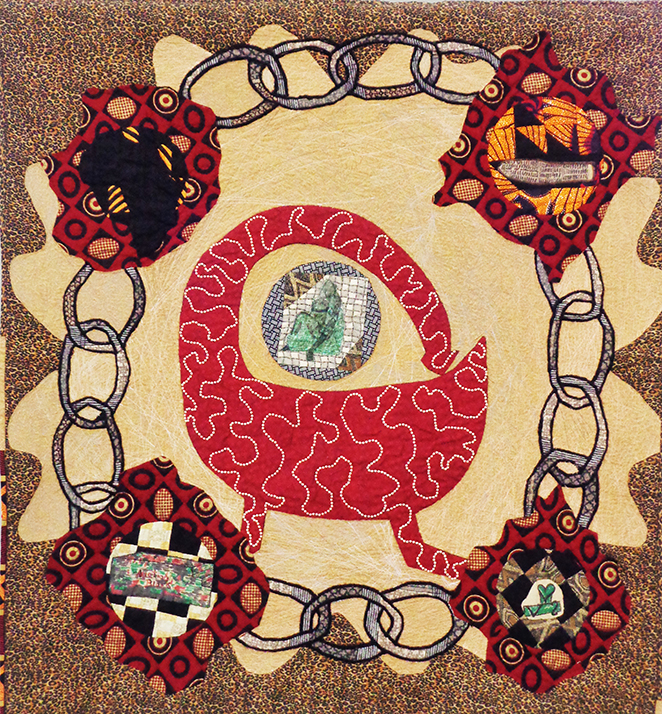

Edna Patterson-Petty’s Slave’s Journey visually speaks volumes using a map of Africa, chains, a slave ship, and a female figure enclosed by Sankofa, an Ashanti symbol of retrieval of the past in the present and upholding heritage for the future. A call to African American and all Africana past so as to understand the present and look forward to the future is captured by Sankofa. Why is an image of a black woman at the center of this magnificent piece? Because the trade in Africana humanity was rooted in exploitation of and animus towards women, Africana women, that were encoded in laws that merged biological function of childbirth with economic and political expediency in slave-owning societies to forge a social phenomenon engrained in culture. If uum walad, a slave concubine bearing a child fathered by her owner in the Muslim world, captures demeaned womanhood and motherhood, European civil law expressed in partus sequitur ventrem, meaning “that which is brought forth follows the belly (womb),” was applied throughout the Americas in British, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Dutch colonies (Adams, 1965; Morgan, 2018). This was exemplified by a law passed by the Virginian General Assembly in the session of December 1662, stating that “negro women’s children to serve according to the condition of the mother”:

WHEREAS some doubts have arrisen whether children got by any Englishman upon a negro woman should be slave or ffree, Be it therefore enacted and declared by this present grand assembly, that all children borne in this country shalbe held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother, And that if any christian shall committ ffornication with a negro man or woman, hee or shee soe offending shall pay double the ffines imposed by the former act. (Hening, 1823)

Thread lines left in the wake of needle repeatedly and violently penetrating quilting fabric in Slave’s Journey, like violence, horrors, and suffering involved in extracting and transporting millions of stolen Africans in the bowels of monstrous slave ships to Europe and the Americas, become a symbol of thousands of horrendous voyages made as the torturous vessels crisscrossed the Atlantic Ocean and also from the East African coast of the Indian Ocean for four hundred years in what is termed “The Triangular Trade” connecting Europe, Africa, parts of Asia, and the Americas in a vicious vortex and a destructive cycle for Africana. Globalization and capitalism, but not democracy, equality, and peace, have their roots in that trade. As an artist and an art therapist, Edna Patterson-Petty transformed the horror and pain Africana suffered, with continuing residues in the present, into a therapeutic artistic message of fortitude, awareness, love, healing, and unity.

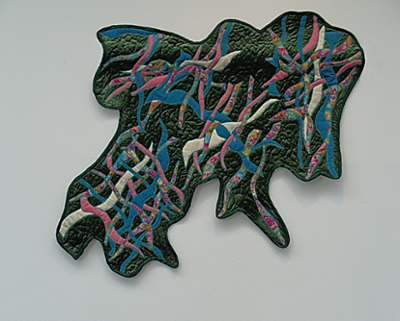

If textile art continues in the Americas, especially among African Americans, it is, just as in Africa, the memory of a people. The art is transgenerational and passed on from generation to generation, each textile art piece a repository of knowledge and aesthetic sensibilities found in other Africana cultural products. Edna Patterson-Petty’s quilts epitomize creativity, consciousness of community and self, and visual eloquence present in African American Art. “Cloth Bwa Hawk Mask” makes the link between African and African American Art not only at the aesthetic level but also on a personal level, in that, African American artists rightly claim their African heritage and employ it intellectually and emotionally to capture totality of the Black Experience. She stated:

I wanted to create something that emulated the wooden version of the mask but in my own media. I have a firm attachment to this mask which is made from raw silk and is adorned with beads and fabric paint. (Patterson-Petty, 2002)

In Edna Patterson-Petty’s quilts and fabric art, the most contemporary modes of communication, including the Internet, are put in the service of improvisation, an enduring aspect of ethos etched on all Africana cultural products. Patterson-Petty’s own words best articulate the process in her creation of Fringe Benefits:

This piece was inspired by a “quilt block” exchange via the Internet. After collecting the blocks, it was a dilemma as to how to display them; so the idea of fringe benefits came to be. The quilt took a lot of time because of the hand stitching, but it was a labor of love. The fringe around the quilt was the icing on the cake (Patterson-Petty, 2002).

If quilts are a memory of a people, it is because those who make them are acutely aware of the life and condition of those they love and care about and use quilts to tell stories of their communities, even a virtual community, but most important of all, the flesh and blood of Africana communities.

In Edna Patterson-Petty’s quilts, for example, in If It Wasn’t for the Women and Slaves Journey, as well as in Nuthin’ But A Feeling, Voice of My Own, Mood Indigo, and In Flight, images and symbols become mnemonic devices in the hands of a master drawing from a millennia-old tradition that demands one to be critical of society but also bask in its achievements and embrace the joys of life. Her quilts, like the Yoruba gelede, transmit didactic messages practiced by story-tellers of the ages, reminiscent of the Akan Ananse, The Spider, or Ewe Eklo or Fon and Yoruba Ajapa, The Tortoise, stories that were transformed and re-interpreted into African American Brer-Rabbit stories on the other side of the Atlantic in America (Owomoyela, 1997). Patterson-Petty, in an artistic voice of her own captured in quilts and mixed media sculpture pieces, stitches, sews, and stamps symbols, like Sankofa and other adinkra symbols, on the fabric of life into consciousness of this generation to be passed on to the next, similar to proverbs that become enduring ancestral memory for coming centuries.

Leonard Gadzekpo

Tuareg Camel Bell

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Tuareg Camel Bell.

C20th. Wood.

5 x 6 x 7 in.

The Reginald Petty Collection.

Botswana Ivory Bracelet

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Botswana Ivory Bracelet.

C20th. Ivory.

5 x 7 in.

The Reginald Petty Collection.

Pieces of the Dream

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty. Pieces of the Dream.

1998. Quilt, Fabric.

48 x 48 inches.

A Slave's Journey

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, A Slave's Journey.

2003.

46 x 43 inches.

Bwa Hawk Mask

Bwa Hawk Mask. Edna J. Patterson-Petty, Bwa Mask.

C20th. Wood. 2001. Quilted Fabric, paint and beads.

8 x 14 x 52 inches. 14 x 6 x 60 inches.

The Reginald Petty African Art Collection

Fringe Benefits

(Photos by Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, Fringe Benefits.

2000. Quilted Fabric.

75 x 100 in.

If It Wasn't For The Women

(Photos: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, If It Wasn’t for the Women.

2011. Quilted Fabric.

34.5 x 35 inches.

Voice Of My Own

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, Voice of My Own.

2006. Quilted Fabric.

29 x 29.5 inches.

Nuthin But A Feelin

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, Nuthin But A Feelin.

2005. Quilted Fabric.

31.5 x 30.5 inches.

Mood Indigo

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, Mood Indigo.

2005. Quilted Fabric.

46 x 43 inches.

In Flight

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, In Flight.

2003. Quilted Fabric.

33 x 29.5 inches.