Memory: Musical Tradition of Africana

/https://dev6.siu.edu//search-results.php

Last Updated: Oct 18, 2023, 03:23 PM

How important is memory to Africana? It is so significant that it spurs improvisation and upholds culture. A generation of Africana, children and grandchildren of Patterson-Petty’s cultural ethos and sensibilities that are yet millennial older, the Hip-Hop generation, values that memory and improvises to claim and retain it. The African drum, banned and denied to their ancestors, may not be readily available to them, but rhythms, the beat, and melodies of the ancients still burst out in their voices amplified and their hands, “scratching” on turntables, electronic drums, electrify in the call and response performance, thus, validate an Africana tradition anchored in the African philosophical base that says: I am because we are. They do sampling, a process of cultural literacy and intertextual reference using technology available, from turntables, through rhythm machines to computers, because the Black or Africana collective memory is at stake, because according to Daddy-O:

You erase our music

So no one could use it . . .

Tell the truth – James Brown was old

Til Eric B came out with ‘I Got Soul.’

Rap brings back old R&B

If we would not

People could have forgot[ten]. (Rose 1994, 89)

Not to forget the past, which is also the present and future, in face of onslaught on the very essence of Africana, not to lose millennial-old cultural literacy, a heirloom carried in the minds of African ancestors to the Americas, Patterson-Petty uses modern materials and techniques to retrieve, re-interpret, claim, and reclaim repositories of spirit and virtues of African/African American ethics and ethos with community in mind.

Memory: Musical Tradition of Africana

42 Days Till You

42 Days Till You visually articulates ancient call and response and improvisational elements in Jazz and in jazz compositions by Mile Davis, a jazz virtuoso, who is a St. Louis native. Edna Patterson-Petty’s quilt is a tribute to him, lest we forget.

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, 42 Days Till You (Miles).

1996. Quilted Fabric and beads.

22 x 20 inches.

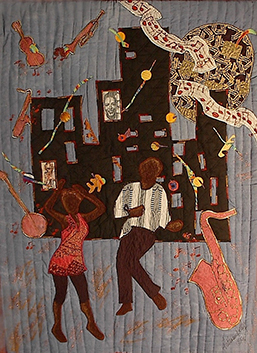

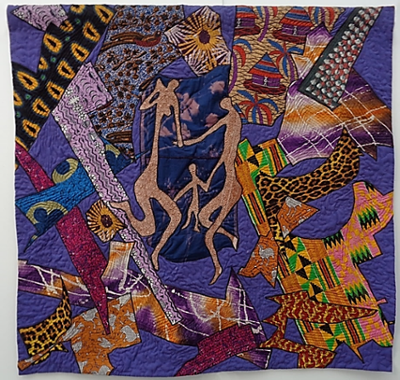

Blues Rendezvous

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, Blues Rendezvous.

1996. Quilted Fabric.

46 x 64 inches.

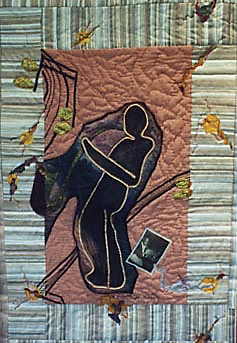

I Got the Blues for You

I Got the Blues for You is a song, a story, and a performance like the Blues, that visually articulates thoughts, emotions, and sensations words could not encompass. In 1960, when Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong went on an African tour with his band, The All-Stars, there were celebrations in all countries where he performed. When he refused to perform for segregated audiences in South Africa, he knew the blues in America and knew that Africans also knew the blues and affirmed to the whole world where he stood when community and humanity of a people, Africana, were at stake. He acknowledged he was of African descent and stated, “I always say a note is a note in any language” (Levin, 2000). John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie, another jazz master and virtuoso with his signature tilted trumpet, valued Afro-Cuban and Afro-Brazilian music, loved African rhythms, and toured with South African singer Miriam Makeba, whose songs were banned in Apartheid South Africa (The Washington Post, 1991). He, thus, affirmed Africana cultural kinship and oneness. Memory is that significant to Black people, Africana, because their culture, survival, growth, and the future depend on it.

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, I Got the Blues for You.

2012. Quilted Fabric.

31 x 32 inches.

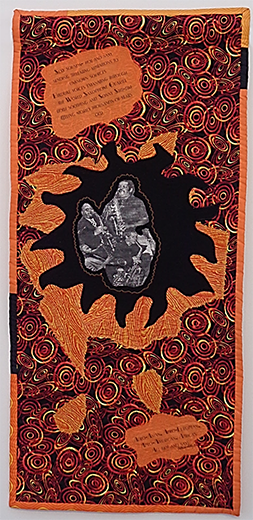

DooBop

But in the Twenty-first Century and for four hundred years, Africana in America still contends with a form of American apartheid, even after Barack Obama’s two-term presidency, given while de jure segregation has been repealed or nullified, de facto segregation persists in access to economic resources, education, housing, criminal justice, healthcare, and other areas, a reality termed systemic racism. As this exhibition was still on display, George Floyd met his untimely death in Minneapolis, Minnesota, under a police officer’s knee on his neck while being held down by other two officers as life slipped out of him on a street curb in a clear and bright summer early evening. Another police officer looked on and warded off people who attempted to intervene to stop Floyd’s demise (Murphy, CNN, 2020). His murder exemplifies persistence of violent deaths of African Americans in the hands of some police officers and other vicious people harboring racial animus. Floyd’s violent death was the latest, preceded by those of Trayvon Martin, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Dreasjon Reed, and McHale Rose, to name just a few. Through the centuries, pain, anguish, suffering, and reckless disregard of Black or Africana humanity generate the Blues. Quilts, just like the Blues, carry a tradition from generation to generation and so too document reality and memory which spawned them to embody intimate personal visual articulation of Africana resistance and cultural values. The Blues and Patterson-Petty’s I Got the Blues for You capture pain, anguish, deep emotions, and thoughts African Americans and all of Africana felt through the centuries and still feel, these being common to all humanity when faced with similar experiences and realities.

DooBop has the same title as one of Miles Davis’ jazz compositions and has his image in it. If Martin Luther King, Jr. believed Jazz was the perfect soundtrack for civil rights, a sensibility Patterson-Petty expresses in Hot and Saxy, it was because Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Stitt, Roland Kirk, Nina Simone, Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, and Sun Ra, to name a few, in their performances and “in commanding stages and demanding to be seen as artists was itself ‘a rebellious political act’ as the scholar Ingrid Monson points out” (Jackson, 2019; Monson, 1999). They contributed not only through their activism but also in financial support to the Civil Rights Movement of the Twentieth Century.

Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, DooBop.

2002. Quilted Fabric.

46 x 64 inches.

Bustin' Loose

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, Bustin' Loose.

2005. Quilted Fabric.

38.5 x 24 inches.

Hot and Saxy

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, Hot and Saxy.

2002. Quilted Fabric.

46 x 64 inches.

Celebrating the Joys of Life

Every generation of Africana creates its performance mode and style built upon ancient African classic tradition and reinterpretations in which “call and response” are the key to cultural continuity. Polyrhythms and melodies are ancient and come from a philosophical underpinning expressed by “I am because we are.” An individual’s heartbeat and voice merge with those of others, like the rhythms and melodies they create, to become the polyrhythms and melodies in Africana performances and all music from ancient to contemporary. Martin Luther King, Jr’s dream is, therefore, linked to the dreams of a people (King, 1992). Langston Hughes asks: What happens to a dream deferred? ( Hughes, 1995). As if to answer the question, Edna Patterson-Petty’s Bustin’ Loose visually inverts the last line and question in Hughes’ poem ‘Dream Deferred,” “Or does it explode?” into a celebration in which Africana musical genius blossoms with petals of talented performers and flaps of cultural reinterpretation boxes open and a myriad of performance genres explode.

Africana performance is also a joy-of-life expression, in that it is for the sake of life as captured in Bustin’ Loose, Hot and Saxy and Celebrating the Joys of Life. In the same vein, Blues Rendezvous could be a “jook joint” in Mississippi, Alabama or Georgia, a jazz club in East St. Louis, Chicago, New Orleans, New York, or Los Angeles. It could be a dance bar in Soweto, Johannesburg, or in other townships in South Africa with Ismail Mohamed-Jan’s, popularly known as Pops Mohamed’s, or Hugh Masekela’s jazz compositions reverberating in the air, with a composition like Stimela or The Coal Train that expresses Masekela’s anguish and protest against exploitation and injustice of the migrant labor system in Apartheid South Africa. The exploitation expressed in Stimela continues in the present affecting the whole subregion and, further in East Africa and Central Africa. It could also be in the pulsating heart of Lagos, Nigeria, in “The Shrine,” where Fela Ransome Kuti’s and his son, Femi Kuti’s Afro-Beat music ripples with “hot and saxy” riffs and fills the air taken in by nightly audiences dancing in perfect rhythm to an array of political and protest songs against police brutality, undemocratic military governments, corrupt civilian governments, injustice and, the list goes on. Across Africa and in the African Diaspora, “jook joints” are a norm. Reginald Petty lived it in Africa and went to a “jook joint”: The Blues, African style. All I could do was shake my head and tap my feet. I felt at home (Petty, 2001).

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, Celebrating the Joys of Life.

1993. Quilted Fabric.

48.5 x 50.2 inches.

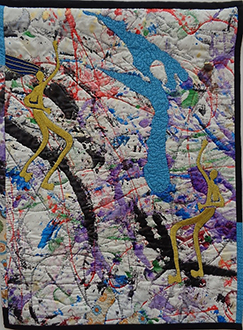

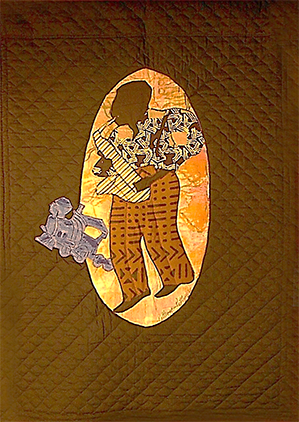

Trane

Edna Patterson-Petty’s Trane pays tribute to another jazz virtuoso, John Coltrane, a “new ancestor,” and generates familial and communal conversation:

I love listening to music as I create. I originally called this piece Take the A-Train, because of the small blue train in the quilt. My husband wanted to name it Coltrane; so we compromised and I named it Trane. At a jazz club, where it was on display last year, a jazz lover said it should be named Blue Trane, because John Coltrane had an instrumental of the same name. So, if nothing else, this quilt has stimulated a lot of conversation. (Patterson-Petty, 2005)

(Photo: Leonard Gadzekpo)

Edna Patterson-Petty, Trane.

2003. Quilted Fabric.

82 x 64 inches.